by Stephen Houston, Brown University

The celebrated Relación of Bishop Diego de Landa (1524–79) offers, in the edition by Alfred Tozzer—a volume in part ghosted, according to rumor, by many Harvard graduate students—a full array of horrors for those who transgressed law and custom in early Colonial Yucatan. Unchaste girls were whipped and rubbed with pepper on “another part of their body” (the eyes, privates or anus?); “offenses committed with malice…[could only be] satisfied with blood or blows,” and those who corrupted young women might expect capital punishment (Tozzer 1941: 98, 127, 231; but see Restall and Chuchiak 2002, who view the Relación as a varied and complex compilation).

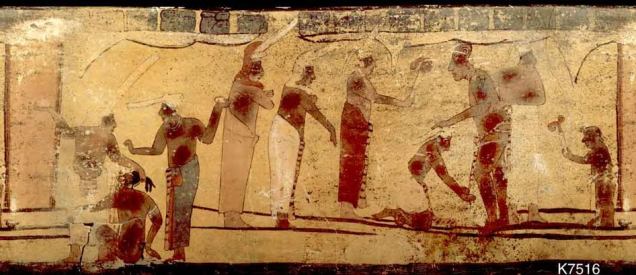

Then there was stoning. If discovered, a male adulterer would be lashed to a post. The unforgiving husband then threw “a large stone down from a high place upon his head” (Tozzer 1941: 124, 215, the latter from Tozzer’s excerpt of Herrera’s Historia General). Other stones played a role in an unusually brutal form of sport attested as far afield as the Cotzumalhuapan sites and various Classic Maya sources (Chinchilla 2009: 154–56; Taube and Zender 2009:197–204). Boxers, “gladiators” even, pummeled each other with stone spheres. Sometimes there was no contest to speak of, and the violence seemed to be inflicted on helpless captives or sacrifices (Figure 1; see also Houston and Scherer 2010: 170, fig. 1).

Figure 1. Stoning of captive, to viewer’s left (K7516, photograph by Justin Kerr, copyright Kerr Associates).

An enigmatic image, related to some unknown tale among the Classic Maya, also involves stoning (Figure 2). A figure daubed with black paint lifts a small white stone that carries the dots and circle of a “stone,” tuun. He is about to wallop a cringing lizard with distinct, backward thrust crest (David Stuart, Marc Zender, and I have read glyphs for this creature as paat, an interpretation we will present at some point). Another figure to the right is poised to jab with what may be a digging stick or coa. Misery will doubtless ensue for the lizard, a fate also awaiting a bound crocodile on a jaguar-skin throne. Maya imagery tends to skirt displays of emotion, but these creatures look downcast, frightened, hopeless.

Figure 2. Torture of mythic reptiles (photograph from Justin Kerr [K9149], copyright holder unknown).

In our recent study of the Grolier Codex, Michael Coe, Mary Miller, Karl Taube, and I presented what seems to us (and to many others) overwhelming evidence for the authenticity of the manuscript (Coe et al. 2015). While working on that project, I was beset with a growing sense of bafflement. Why did anyone question the Codex to begin with? On dissection, the objections seemed ill-founded and argued.

Here is another piece of evidence (Figure 3). Page 9 of the Grolier shows a mountain deity grasping a stone, a point made also by John Carlson (2014: 5). Perceptive as ever, Karl Taube, who authored this part of our essay, noted that such weapons were used as punishment (Coe et al. 2015: 154). But beyond castigation, there is surely a martial aspect to the pages of the Grolier, of spearing, slicing, and thrusting with atlatl darts. Death by hand-held stone is a particularly messy way to go. The white stones must have contrasted vividly with the blood and gore that streaked them.

Figure 3. Grolier Codex, page 9 (drawing by Nicholas Carter, Coe et al. 2015: fig. 41).

What we did not emphasize enough, perhaps, was that other scenes of such execution or torture were simply not known or understood in the Classic corpus when the Grolier was found in the early to mid-1960s. Almost all the images documented by Justin Kerr and presented here were not recognized as such until a few years ago. That applies equally to most of the imagery interpreted by Chinchilla Mazariegos, Taube, and Zender as boxing or sacrifice with hand-held stones.

I am confident that such evidence will only accumulate as our understanding deepens and the Grolier continues to release its secrets.

References

Carlson, John B. 2014. The Grolier Codex: An Authentic 13th-Century Maya Divinatory Venus Almanac: New Revelations on the Oldest Surviving Book on Paper in the Ancient Americas. The Smoking Mirror 22(4): 2–7.

Coe, Michael, Stephen Houston, Mary Miller, and Karl Taube. 2015. The Fourth Maya Codex. In Maya Archaeology 3, edited by Charles Golden, Stephen Houston, and Joel Skidmore, 116–67. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, San Francisco.

Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo. 2009. Games, Courts, and Players at Cotzumalhuapa, Guatemala. In Blood and Beauty: Organized Violence in the Art and Archaeology of Mesoamerica and Central America, edited by Heather Orr and Rex Koontz, 139–160. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles.

Houston, Stephen, and Andrew Scherer. 2010. La ofrenda máxima: el sacrificio humano en la parte central del área maya. In Nuevas Perspectivas Sobre el Sacrificio Humano entre los Mexicas, edited by Leonardo López Luján and Guilhem Olivier, 169–193. UNAM/INAH, Mexico City.

Restall, Matthew, and John F. Chuchiak. 2002. A Reevaluation of the Authenticity of Fray Diego de Landa’s Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan. Ethnohistory 49(3): 651–669.

Taube, Karl, and Marc Zender. 2009. American Gladiators: Ritual Boxing in Ancient Mesoamerica. In Blood and Beauty: Organized Violence in the Art and Archaeology of Mesoamerica and Central America, edited by Heather Orr and Rex Koontz, 161–220. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles.

Tozzer, Alfred M. 1941. Landa’s Relación de las Cosas de Yucatan: A Translation. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology 18. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.