The Spaniards expressed a certain ambivalence about Maya glyphs. They called them letras, a neutral word suggesting an equivalence to their own writing system. But they could also describe the script in terms of caracteres. This implied, among other nuances, a cipher or emblem of magical import (Drucker 2022:61–62; Hanks 2010:3).[1] At the time, charaktêres, an obvious cognate with caracteres, were mystical signs created by adding circles or other embellishments to preexisting scripts (Gordon 2014:266–67). Devoid of grammar, often written for single use, they were thought to be “unutterable,” being visionary in origin and direct conduits to mystical meaning (Gordon 2014:263). John Dee, the Elizabethan-era occultist, even claimed to have received his own esoteric script from angels (Harkness 1999:166). Maya glyphs, by contrast, were understood to be legible if challenging to read. Like other writing, they recorded, among their quite varied content, “the deeds of each king’s ancestors” and reports of “years, wars, pestilences, hurricanes, inundations, hungers” (Houston et al. 2001:26, 40).

But the Devil was seldom far away. Missionaries and colonial authorities recognized that glyphs served a role in enchantment and conjuring (Hanks 2010:8; Houston et al. 2001:36). The destruction and confiscation of books—the focus was not on the stone carvings from centuries before the Conquest—would, according to the Franciscan Bernardo de Lizana, writing in 1633, “cure and cauterize the pestilential cancer [of idolatry] that was eating away at the Christianity that [the friars] had planted with such great effort” (Chuchiak 2010:91). Diego de Landa had paved the way a few generations before: “[w]e found a great number of books of these letters of theirs, and because they had nothing but superstitions and falsities of the devil (demonio), we burned them all, which they felt amazingly and gave them great sorrow” (Landa 1959:105, translation ours, from scanned version by Christian Prager; see also Restall et al. 2023:164; Landa used demonio, “demon,” as a singular and collective noun, for it could apply both to Lucifer and individual Maya gods, including Hunhau [from Hun Ajaw, presumably], said to be the “prince” [príncipe] of them all [Landa 1959:60]). The shift to Latin script, even for esoteric works out of Spanish control, showed how obnoxious the glyphs had become to Spanish authorities and to local scribes wishing to employ a (by then) more prestigious script when integrating Maya and Christian beliefs (Chuchiak 2010:106).

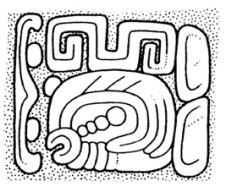

Thoughts about devilish writing bring to mind a text, from Europe but approximately the same time, said to have been written by the Devil himself (or, more precisely, an “archfiend” named Per Talion, Ansion et Amlion [Clark 1891:497–499]; see also Drucker 2022:105, fig. 4.9]). This appears in Teseo Ambrogio degli Albonesi’s Introductio in Chaldaicam lingua[m], Syriaca[m], atq[ue] Armenica[m], & dece[m] alias linguas (original here), 1539, 212r (Figure 1). Ambrogio received a report of this document, supposedly in the demon’s own hand, after the fiend was conjured by one Lodovico de Spoletano. The demon was asked to respond to a money-grubbing query, suitable for the corruptor of venal souls… and in Italian no less, perhaps his notional language! The question: Sel Cavaliero Marchantonio figliolo de riccha donna da Piacenza ha ritrovati tutti li dinari che laso Antonio Maria, et se no in qual loco sono?; “has Cavaliero Marchantonio, son of a rich woman from Piacenza, found all the dinars that Antonio Maria left, and if not where are they?” (Hayden 1855:189).

The pitchfork script and swirling tails point to their purported maker. The way the tails transgress lines hints at some aggressive property of the “writer” and may also establish links between different parts of the text. Generally, a vertical and horizontal orientation guides the pitchforks, separated by the occasional dots, in sets of 1, 3, and 4, or jagged lines of 1, 2, 3 and 4, and a few signs shaped like Xs. The final sign with whiplashing tail, looks vaguely like the astrological sign of Taurus or the planet Mercury. If there is code here, it is seemingly written from left to right, like Latin script. That reading order is confirmed by the shorter, final line, which fails to reach the right side. The lines contain respectively (and somewhat approximately, given the challenge of counting individual signs), 31, 28, 22, 25, 21, 24, and 16 signs, for 143 graphs in total, a wordy response to a question of some 118 letters. (The reading order is confirmed by the shorter, final line.) Out of the entire sequence, only one set of signs appears to repeat, the 10th and 11th from the left in the second row, but that may be from the imperfect application of ink in the block made for this illustration (see the smear of pigment to the upper left). A rough typology of signs, much affected by whether a missing tine is intended or not, or a flange or dot, reaches about 35 signs, the upper range of an alphabet; the inverted pitchfork without central tine may be among the most numerous, coming to some 10 examples. To an intriguing extent, the use of similar signs that find contrast by orienting right, left, up, down, resembles Sir Thomas More’s Utopian alphabet from 1518 (Figure 2). More’s shapes, likely devised by his printer and friend, Pieter Gillis of Antwerp, were influenced by geometrical concepts of the Humanist Renaissance, with a greater number of “closed” forms than evident in the Devil’s pitchforks (Houston and Rojas 2022:251; see also Campbell et al. 1978).

Also the work of the Devil, at least by far later report, is the Bohemian Codex Gigas, now in the National Library of Sweden. In 1638, during the 30 Year’s War, it was seized by Swedish troops from the collections amassed in Prague by the Emperor Rudolf II. Eventually, it made its way to the royal library in Stockholm. This unusually large book, 89 x 49 cm, consisting of 310 parchment leaves, was made between AD 1200 and 1230 (Figure 4). A popular account insists that the image was painted in homage to the Devil, who assisted in its production, or that it might even have been made by his hand. This fable, emphatically denied by the National Library, is not quite the same as the stories from Ambrogio and Sister Maria, for the image of the Devil, unusual for its frontal position, sits across from an image of Jerusalem. When the book was open, he would squirm across from the city; when closed, his body would collapse into it. Fascination with the image has led to its over-exposure and fading, as can be seen by comparing the two images below.

That the Devil was literate, assumed to be capable of polite missives and written colloquies, doubles back to Maya glyphs and Spanish views of them. Those works were just as impenetrable, just as unreadable, as the “characters” confronting Ambrogio and Sister Maria: the Maya books were best burned, or sent as idle curiosities to be viewed back in Europe with interest and, perhaps, trepidation.

Note 1. See the Oxford English Dictionary, with a citation from John Metham, 1449, writing in Middle English, “Anone he dyght hys sacrifyse..hys cerkyl gan dyuyse With carectyrs and fygurys, as longe to the dysposycion Off tho spyrytys.”; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “character (n.)”; Singer 1989:53; see also Hamann 2008:35, on these “abstract and esoteric and asonic” fantasies).

Appendix 1. Describing the Devils’ writing

Non tam cito pennam Magus deposuerat, quam cito qui aderant pennam eandem corripi, et in aera sustolli, et in eandem charta infra scriptos characteres velociter scribere viderunt scribentis vero manu nullus comprehendere potuerat Ut mihi aliquem retulit, qui cum multis presens fuer[at et] cum postmodum Papiam venisset, et factum ut fuerat enarraret. Rogatus archetypum mihi reliquit. Cuius verba adscripsi. Characteres vero tales erant. Quid vero characteres illi insinuarent, quam[ve] responsionem ad quaesita redderent scire o[mn]ino non curavi Quandoquidem vanas Magorum superstitiones, et somniis similia deliramenta, naturali quodam semper odio prosecutus fuerim. Nec mihi quispiam persuadere umquam potuerit, ut talia placerent. Non enim me latuit, huiusmodi nequam spiritus, suis semper cultoribus, laqueos tendere, ut irretintos in perniciem trahent. Exemplo nobis iamdudum esse potuit (ut multos praeteream) antiquus ille Simon Magus, qui Apostolroum temporibus misere interiit.Et in presentia hic, de quo loquimur, qui paulo ante, cum se rei militari totum dedisset, ac sub eius vexillo armatos tercetnos, sive quadrigentos duceret pedites, in rusticorum semel manus incidit. Qui tot illum ferris tridentibus (quot invocatus Amon, in suis characteribus effinxerat), appetentes, percusserunt, vulneraverunt, transfixerunt, Et tricipiti apud inferos Cerbero consignandum, mulits undique laeatalibus cribratum vulneribus, exanime tandem corpus ille reliquerunt. Verum cum in dignoscendis variarum linguarum characteribus, ac literarum figuris, propenso semper animo versarer, nolui etiam hoc scribendi genus, pratermittere intactum …

No sooner had Magus put down the quill than those who were present saw that same quill being grabbed and being borne in the air, and [they saw that quill] on the same sheet writing quickly writing the characters below. Yet the hand of the one writing no one could perceive. So he brought me someone, who had been present with many [others] and had just come to Papia. And he related how the deed had happened. Having been asked, he left me the archetype [i.e., the original manuscript], whose words I wrote down.— Such indeed were the signs: As to what those characters actually insinuated, and what response they gave to the questions asked I did not care to know at all, especially since with a certain natural hatred I have always chased away the empty superstitions of “Magicians” and their delirious visions similar to dreams. And no one has ever persuaded me that such things were acceptable. For it does not escape me that such evil spirits lay snares for those who worship them that they may drag them entangled into ruin. That famous Simon Magus, who died a miserable death in the days of the Apostles, can serve as an ancient example for us—I pass over many others [in silence]–this man of whom we speak, who a little before, had devoted himself entirely to military matters, and led three or four hundred footmen armed under his standard, once fell into the hands of peasants, who sought him, struck him, wounded him, and pierced him with as many tridents of iron (as the invoke Amon had represented in his characters). Having been consigned to the triple-headed Cerberus in the underworld, wounded on all sides by fatal wounds, they finally left his body lifeless. Since in distinguishing the characters of various languages, and the shapes of the letters, I ponder them with an ever attentive mind, I did not want to pass over this kind of writing undiscussed …

References

Campbell, Lorne, Margaret Mann Phillips, Hubertus Schulte Herbrüggen, and

J. B. Trapp. 1978. Quentin Matsys, Desiderius Erasmus, Pieter Gillis, and

Thomas More. Burlington Magazine 120:716–25.

Chuchiak, John F., IV. 2010. Writing as Resistance: Maya Graphic Pluralism and Indigenous Elite Strategies for Survival in Colonial Yucatan, 1550–1750. Ethnohistory 57(1):87–116.

Clark, Andrew. 1891. The Life and Times of Anthony Wood, Antiquary of Oxford, 1632-1695, Described by Himself, Volume 1, 1632-1633, pp. 497–99. Oxford: Oxford Historical Society.

di Lampedusa, Giuseppe. 1960. The Leopard, trans. by Archibald Calquhoun. London: Collins and Harvill.

Drucker, Johanna. 2022. Inventing the Alphabet: The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gordon, Richard. 2014. Charaktêres Between Antiquity and Renaissance: Transmission and Re–Invention. In Les savoirs magiques et leur transmission de l’Antiquité à la Renaissance, edited by Véronique Dasen and Jean–Michel Spieser, pp. 253–300. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo.

Hamann, Byron E. 2008. How Maya Hieroglyphs Got Their Name: Egypt, Mexico, and China in Western Grammatology since the Fifteenth Century. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 152(1):1–68.

Hanks, William F. 2010. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harkness, Deborah E. 1999. John Dee’s Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Houston, Stephen D., Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, and David Stuart, eds. 2001. The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

———–, and Felipe Rojas. 2022. Sourcing Novelty: On the “Secondary Invention” of Writing. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 77/78:250–66.

Hayden, Henry H. 1855. “Mysterious Scrawl” in Queen’s College, Library, Oxford. Notes and Queries 11:159.

Kircher, Athanasius. 1652–1654. Oedipus Aegyptiacus, 3 vols. Rome: V. Mascardi.

Landa, Diego de. 1959. Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. Biblioteca Porrúa 13. Mexico City: Editorial Porrua.

Langeli, Attilio B. 2020. Scritture nascoste scritture invisibili, ovvero: Giochi di prestigio con l’alfabeto. La Bibliofilía 122(3):557–72.

Restall, Matthew, Amara Solari, John F. Chuchiak IV, and Traci Ardren. 2023. The Friar and the Maya: Diego de Landa and the Account of the Things of Yucatan. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

Singer, Thomas C. 1989. Hieroglyphs, Real Characters, and the Idea of Natural Language in English Seventeenth Century Thought. Journal of the History of Ideas 50:49-70.

Tozzer, Alfred M. 1941. Landa’s Relación de las cosas de Yucatán: A Translation. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology XVIII. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Yeowell, J. 1855. “Queen’s College, Oxford.” Notes and Queries 11:146.

You must be logged in to post a comment.